By Leo Manolis

Woking: to outsiders, it’s a stopover to London or Guildford; to those of us who live here, it’s a stopover to London or Guildford. Despite our apparent irrelevance, as someone who lives in Woking, I can’t help but feel a degree of endearment towards this hub for anti-social behaviour and sometimes aggressive pubescents. Which led me to wonder how exactly my glorious hometown came to be; how was Woking founded?

To be clear, this article won’t be about the entire history of Woking: records of the town stretch as far back as the Domesday book, where it was called “Wochinges”. In the interest of time, I’m focusing solely on the 19th– century developments which led to Woking becoming the town it is today: it’s an extremely dodgy story of dead bodies and criminal institutions. No, seriously.

Now, you can imagine my surprise to learn that Brookwood Cemetery in Woking is the largest in the United Kingdom, one of the largest in Europe, and once, the largest in the world. I think anyone would be surprised to learn that the cemetery and its founders were indirectly responsible for the development of the Woking we all know and feel somewhat lukewarm towards today.

Woking’s story begins in the late 1840s. In 1848–49, London endured a cholera outbreak that killed approximately 15,000 people. Urbanisation and population growth as a result of the Industrial Revolution meant that pathogenic outbreaks like this were becoming increasingly regular, and London just wasn’t able to bear the mounting pressure from the sheer number of dead bodies. Existing burial grounds and cemeteries were overcrowded, and something had to be done. Taking advantage of what was then still a sensational new technology – trains – some entrepreneurs proposed that bodies should be transported by railway to a cemetery in the countryside. Because looking at widespread grief and dead bodies and wondering, “How can I monetise this?” was a truly Victorian activity.

From the outset, the project attracted opposition. Hansard records the Earl of Shaftesbury challenging the company’s estimates, saying, “The calculation of this company was, that it would be able to secure for itself one-half, if not two-thirds, of the corpses of persons dying in and about London… this was an exaggerated calculation. If it could not secure 30,000 or 40,000 corpses annually, it would not be able to meet its preliminary expenses.” Moreover, The Morning Post of 22 May 1852 quoted Viscount Ebrington calling the plan “perfectly preposterous,” arguing that London still had enough burial space. The idea of moving dead people away from their home city, local church, or place of death more generally, was quite repulsive to British society at the time.

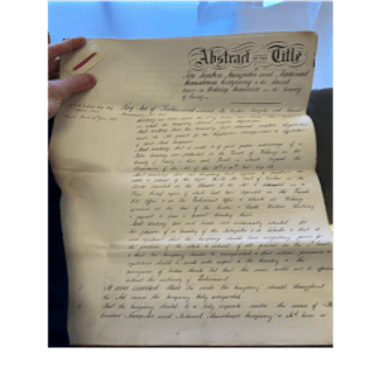

Nevertheless, this idea was formally taken up by Sir Richard Broun and Richard Sprye, who chose the obscure town (village, really) of Woking as the site for the cemetery, thanks to its cheap land and ‘goldilocks’ proximity to the capital. In the Surrey Archives (which I highly recommend visiting) I found their Memorandum Of Agreement, recording their provisional registration of the London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company on 5 February 1850 as a joint-stock company valued at £250,000. It documents their negotiations with Southwestern Railway, and also sets out their meetings with the Earl of Onslow, who will become relevant in just a moment.

Parliament addressed the issue with its London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Act in 1852. The Act authorised the company to acquire land for the cemetery and required South Western Railway to transport the bodies and mourners once the cemetery was operational.

The company then moved to secure the necessary land. Its agreements with the Earl of Onslow show the scale of purchase: 2,000 acres in Woking for £35,000. The price was set at £20 per acre for 1,500 acres and a discounted price of £10 per acre for 500, in consideration of a planned chapel being built there, and also because Broun and Sprye sweetened the deal by promising to name the chapel after the Earl of Onslow, granting him the hereditary ceremonial position as president of the company. Interestingly, I also found a declaration by a local Yeoman, Richard Drewiitt, who had to attest to the fact that the land in question was actually owned by the Earl of Onslow: “I have for 48 years now past known the land tournaments and hereditary forming the manner of Woking in the county of Surrey that I have examined the map or plan annexed to a deed. And I make this solemn declaration conscientiously believing the same to be true.” On top of buying land from the Earl of Onslow, they also decided that they’d have to buy up land from the people of Woking, as well as removing their rights of common to the land: In 1854, the company paid the commoners of Woking £15,000 – equivalent to £1,827,814.80 today – to extinguish these rights.

The company also produced construction plans. A surviving map by Henry Robert Abraham shows proposed layouts, substituted footpaths, and diverted roads. Brookwood Cemetery was completed in 1854 and open from the 13th November of that year. The first train ran in November that year: The Times advertised daily funeral services, with a first-class grave costing £2.10 and a second-class grave £1.00, including both the train journey and chapel service.

However, the company quickly encountered a problem: it had bought far, far, far too much land. The company had purchased about 2,200, but only required 400 for the cemetery. The sale of the remaining land became a major factor in the development of Woking. Once again, Parliament intervened: the 1855 London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Amendment Act permitted the company to sell surplus land, and the 1869 Amendment Act removed remaining restrictions. The company began to sell land, first as residential plots, – the 1857 development plan shows how plots were laid out for sale – and later to other companies and institutions: in 1859 the Woking Invalid Convict Prison was built on about 64 acres purchased from the company, and later became Inkerman Barracks; in 1867 the first purpose-built women’s prison in the United Kingdom was constructed on another section of land sold by the company; in 1864, after a visit from the committee of visitors of the Lunatic Asylum of Brookwood, the Country Pauper Lunatic Asylum was established, later becoming Brookwood hospital. The construction of these institutions required labourers to migrate to the area, housing to be built for them and their organisers, the construction of brick kilns, the migration of permanent employees of these new institutions, and a general development of the Woking area.

Census data demonstrates the resulting demographic change: between 1841 and 1851 Woking’s population grew by 14.3 percent; between 1851 and 1861, after land sales had tentatively begun, the increase was 34.6 percent; between 1861 and 1871, after many of these institutions were constructed and residential plots sold, the population increased by 72.5 percent.

Together, these records show how a company formed by Broun and Sprye to solve a burial crisis, which somehow ended up leading to the formation and development of Woking as we know it today. Just imagine: the Woking we know began with a massive cemetery, a lunatic house, and a bunch of prisons: a true embodiment of the amazing town Woking was to become.